Article

Feb 12, 2026

We’ve been evaluating what a “good” policy looks like from the wrong perspective.

Across technology, and especially in Trust & Safety, policy debates tend to degrade into a referendum on a single, emotional outcome:

Did people like the takedown?

Did the creator complain?

Did the press write a story?

Is “the internet” mad?

None of that measures policy effectiveness. It only measures the political cost of a decision.

Policy effectiveness is actually simpler—and far more rigorous: Did we execute the policy faithfully?

This implies a crucial question: can we even tell whether the policy was executed faithfully? If the answer is no, it’s not a policy—it's merely a preference.

This is the central challenge that Trust & Safety teams have wrestled with for a decade. A platform publishes a policy: “We prohibit hate speech, harassment, and harmful content.” Surely everyone agrees with this sentence, right?

Then, the first difficult case arrives: a user posts a slur in a quote to condemn it; a marginalized creator reclaims a term; or a comment uses coded language that is hateful, but not technically explicit.

The real measure of policy effectiveness is not public sentiment. It is:

Can two different reviewers apply the policy and consistently arrive at the same result?

Can the platform explain the decision without inventing a new rule mid-stream?

Can enforcement scale beyond a small team of high-context experts?

Can it be done consistently when content is emotionally charged and time-sensitive?

When the answer is no, the policy isn’t failing due to poor execution. It’s failing because the policy was never precisely specified in the first place.

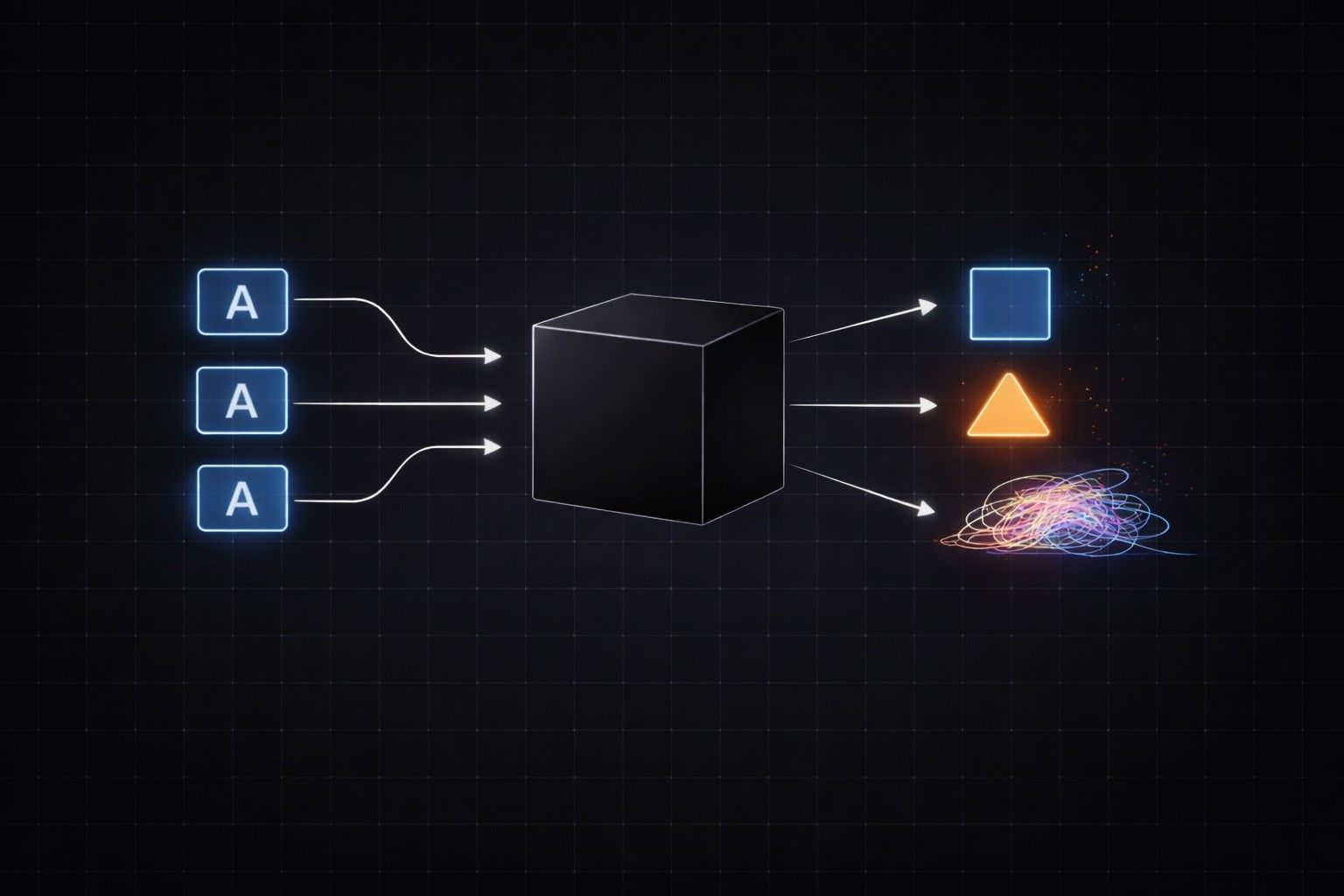

This failure mode isn’t limited to just T&S—we’re seeing the same mistakes made with guardrails for agentic AI where the results could be catastrophic:

Consider a system like OpenClaw: an autonomous agent that can run on your machine, read files, execute commands, and initiate financial transactions. When dealing with something that can act in the real world, the problem is not choosing the right values; it’s ensuring the policy governing that agent is reliably executable.

In short, we need to define our policies in ways that are executable, not:

“safe in spirit."

"aligned with our mission."

"reasonable if you squint."

If your "policy" for an AI agent is a high-level list of values—"don't do harmful things," "don't access sensitive files," "don't spend money without permission"—you are in the exact same situation that has led to endless debates in the T&S world.

And personally, I’ll just say this: To me, interpretation is the last thing you want to outsource to a system with access to your filesystem, credentials, and credit cards.

To make “executable” concrete: a rule isn’t just a sentence. It has a structure.

For agentic systems, an executable rule typically needs:

The target/context: what the rule is acting on (a tool call, a file read, an outgoing message, a payment intent)

The applicability gate: when the rule runs (only for certain tools, certain directories, certain actions)

The decision: a check that can be evaluated to a clear allow/deny (or “escalate”) outcome

The enforcement: what happens when the rule fires (block, require confirmation, downgrade permissions, log)

It needs explicit definitions for the terms inside it. For example, “allowlisted directory” is only meaningful if you define how paths are resolved, how symlinks are handled, and what counts as a sensitive file.

And crucially: an executable policy needs a defined behavior for uncertainty. "I'm not sure" can't be an unhandled state in a system that can act independently.

This is what it means to turn values into constraints.

We often act like the hard part of governance is choosing the right ethical principles. But the truly hard part is whether those principles can be turned into boundaries that execute faithfully—at machine speed, in the real world.

When you look at your policies, don’t ask “will people be ok with this?”

Ask: “Could I execute this policy tomorrow, with a different reviewer, at 10x the volume, and end up with the same outcome?”

If you can’t answer yes, you don’t have a policy. You have a set of values.

And values are not a control surface.

Looking at policy from this perspective changed how I evaluate a “good” policy. More importantly, it revealed how often our “policies” are unfinished.

I acknowledge that the work to make a policy executable isn’t easy. It requires more thought, more detail, more precision in how we use language and how we decide what context is important. It requires follow up to observe the results, identify gaps, and then iterate.

But given the ever-rising stakes, it’s worth doing properly.

Get to know Clavata.

Let’s chat.

See how we tailor trust and safety to your unique use cases. Let us show you a demo or email us your questions at hello@clavata.ai